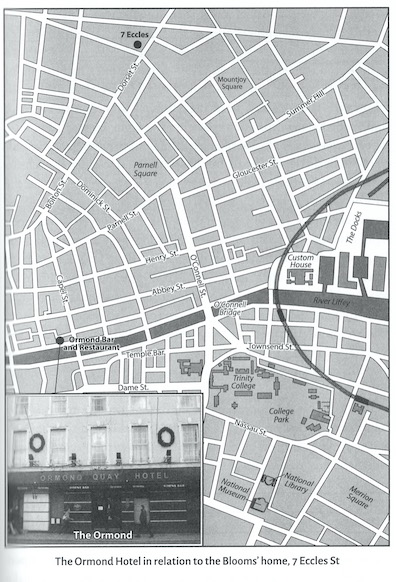

Episode 11, "Sirens," takes place between 4 and 5

PM, most of the action happening in the bar, restaurant, and

"saloon" (a small concert space) of a

hotel on the northern quays

where Bloom sees Blazes Boylan depart for his assignation with

Molly. From passages in book 12 of the

Odyssey, Joyce

conceived some key narrative elements: two beautiful and

seductive young women, some emotionally compelling songs, a man

listening from afar, threats of destruction. He made this a

chapter about music, just as

Hades is about death,

Aeolus

about rhetoric, and

Lestrygonians about eating. In

addition to representing the performance of several actual songs

(nearly every word of

one

appears in the text),

Sirens is composed of words that

aspire to the condition of music. Through repetition,

onomatopoeia, alliteration, assonance, fragmentation, rhythmic

organization, and other devices, words are freed from rigidly

sematic contexts and converted into quasi-musical motifs. Joyce

was deluded in his pretentious claim to have created the

equivalent of a baroque fugue, but he beautifully succeeded in

blurring the boundary between literature and music.

In one passage of book 12, Circe tells Odysseus how to

listen to the seductive song of some sea nymphs without being

destroyed. In another part of the same book, the hero follows

her advice. The Greek mythological figures called Sirens do

not appear in any existing classical literature before the Odyssey,

and Homer does not describe, number, or name them. Only three

things are certain: they are female, they inhabit a coastal

plain, and they lure sailors to destruction by singing

"piercing songs. Around about them lie / great heaps of men,

flesh rotting from their bones, / their skin all shriveled up"

(12.45-47, trans. Wilson). Circe tells Odysseus that when his

ship passes by this coast he should plug his men's ears with

wax and have them bind him tightly to the ship's mast so that

he can hear the beautiful music without succumbing to its

seductive lure. The hero exactly follows her advice, gaining a

rich experience while bypassing a mortal peril.

As in many other chapters in Ulysses, a short but

imaginatively rich incident generates a wealth of imagistic

details. Two attractive young women work behind a bar

described as a "reef of counter," in "cool dim

seagreen sliding depth of shadow." One of them has just

returned from a seaside vacation, "Lying out on the strand

all day.... Tempting poor simple males," and she

has brought back a lovely seashell, a "spiked and winding

seahorn" (probably a conch) that makes haunting sounds when

held to the ear. Darting to the window to see a young man in

the viceregal cavalcade who is turning to look at her, she

laughs through "wet lips" and tells her companion that "He's

killed looking back.... Aren't men frightful idiots?"

Other men enter the bar and flirt with the women, and

eventually three of them perform well-known songs to piano

accompaniment, in front of "a dusty seascape" depicting "A

headland, a ship, a sail upon the billows.... A

lovely girl, her veil awave upon the wind upon the headland,

wind around her." From his perch in the dining room next

to the bar, Leopold Bloom listens to the songs, watches the

women listening to them and to the seashell, and thinks of "lovely

seaside girls." Unwinding an "elastic band," he weaves

it around his fingers in some kind of cat's cradle, leaving

them "gyved...fast" like Odysseus to his mast.

Aeolus, fabricated from imagistic reminders of

Homer's story about the winds and the rhetorical devices that

are their everyday equivalent, quotes from three actual

speeches exemplifying Aristotle's three kinds of rhetoric. In

Sirens the imagery suggestive of Homer's seductive

nymphs is complemented by three actual songs of "Love and

War." As Bloom listens to them, emotion wells up in

him—understandably, since Molly has told him that Boylan will

be coming to see her "at four" (the hour when the chapter

begins) and Boylan makes an appearance at the Ormond Hotel bar

on his way to Eccles Street. Bloom becomes an Odysseus figure

both by being susceptible to these rushes of strong emotion

and by distancing himself from them. He thinks about music

with critical detachment, musing in his wry layman's way on

its calculating devices and mysterious powers.

Joyce too was thinking abstractly about music as he wrote the

chapter, and more ambitiously, though it seems likely that his

knowledge of musical theory was little better than Bloom's.

Ellmann records remarks that he made to Georges Borach on 18

June 1919: “I finished the Sirens chapter during the last few

days. A big job. I wrote this chapter with the technical

resources of music. It is a fugue with all musical notations:

piano, forte, rallentando, and so on. A quintet occurs

in it, too, as in Die Meistersinger, my favorite

Wagnerian opera…. Since exploring the resources and artifices

of music and employing them in this chapter, I haven’t cared

for music any more. I, the great friend of music, can no

longer listen to it. I see through all the tricks and can’t

enjoy it any more” (459). The disenchantment was probably

temporary, but the grandiose affectation was only too

enduring. Ellmann goes on to remark that Joyce later went with

Ottocaro Weiss to see Wagner's Die Walküre, and at the

intermission he asked his friend, "Don't you find the musical

effects of my Sirens better than Wagner's?" When Weiss

said no, "Joyce turned on his heel and did not show up for the

rest of the opera, as if he could not bear not being

preferred" (460).

Sirens displays many impressive quasi-musical effects,

but Joyce's efforts to treat it as a genuine musical

masterpiece seem pretentious and defensive. Whatever he may

mean by a "quintet"—probably the moment when "Lidwell, Si

Dedalus, Bob Cowley, Kernan and big Ben Dollard," "true men"

all, lift glasses—it can hardly be equivalent to what Wagner

does. Effects like piano (quiet), forte

(loud), and rallentando (gently slowing down) are so

laughably basic as to demean anyone who prides himself on

using such "technical resources." Most pretentious of all is

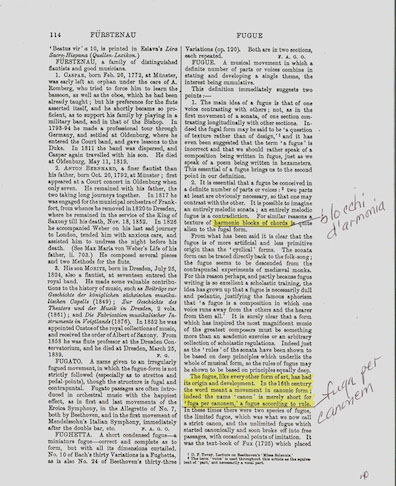

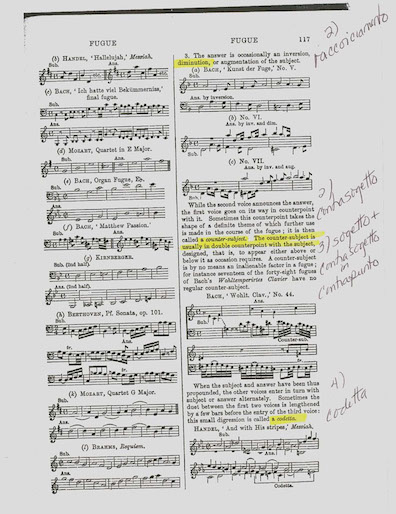

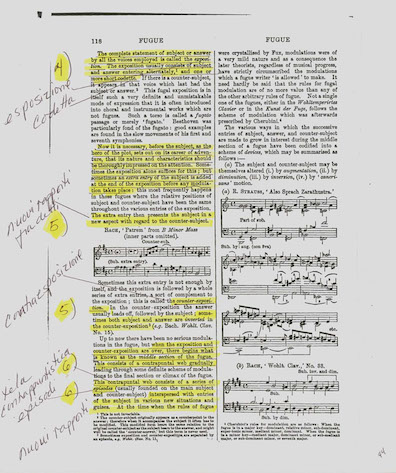

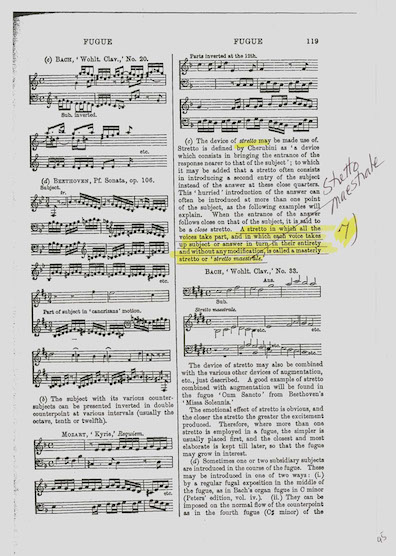

the claim to have written a fugue. In both schemas Joyce

identified the Technic as "Fuga per canonem," and in a letter

he told Harriet Shaw Weaver that the chapter had "all the

eight regular parts of a fuga per canonem" (Letters

1.129). Notwithstanding the fact that this is not a commonly

recognized term in musical theory ("fugue" is, but per

canonem?), literary critics have been all to willing to

hear in this authorial boast an indication that Sirens

possesses some dauntingly intricate structure. Many have

labored to explain how the prose exemplifies it, prompting

many others to mindlessly repeat the critical mantra: fuga

per canonem....

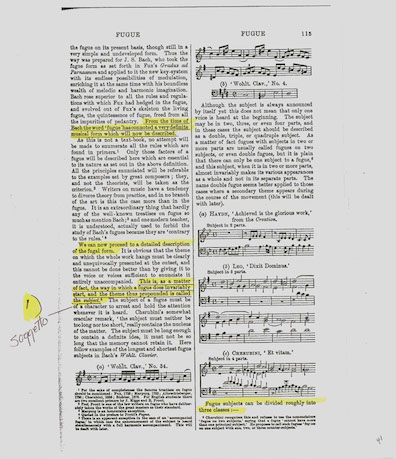

This whole critical endeavor has the feel of a snark hunt.

Literary texts, which move forward one word at a time, simply

cannot reproduce the contrapuntal effects of a fugue, in which

multiple melodic lines sound simultaneously, pursuing separate

horizontal paths but coinciding vertically in harmonious

intervals. Poetry and prose fiction can certainly accomplish a

complex interweaving of themes, and they can be contrapuntal

in the loose sense of having different voices answer one

another successively, but they cannot do so

simultaneously. To achieve true contrapuntal polyphony in the

medium of language, speakers would have to perform separate

texts at the same time—a kind of supra-literary vocal

performance art which Sirens does not attempt.

One might argue that Joyce's per canonem implies

something simpler. A "canon," or "round," is a more basic

contrapuntal form in which a melody is repeated unchanged over

and over again. Such songs (Three Blind Mice, "Row,

row, row your boat," Frère Jacques) are far less

complicated than the fugues written by Bach and other Baroque

composers, but they too are impossible to replicate in a

literary medium. And Joyce's strange reference to the "eight

regular parts" of a fugue suggests that he was thinking of

something decidedly un-simple.

Susan Brown has offered to dispel the air of grandiosity in

Joyce's self-advertisements, and to undermine the critical

hunt for intricate contrapuntal structure in Sirens, in

an article titled "The Mystery of the Fuga Per Canonem

Solved," published first in Genetic Joyce Studies 7

(2007) and then in European Joyce Studies 22 (2013):

173-93. As a result of scrutinizing one page in a long-lost

trove of Joyce's manuscripts and notes, Brown reports that

Joyce's notion of a fugue in eight "regular parts"—a

theoretical entity that no musician has ever heard of—came

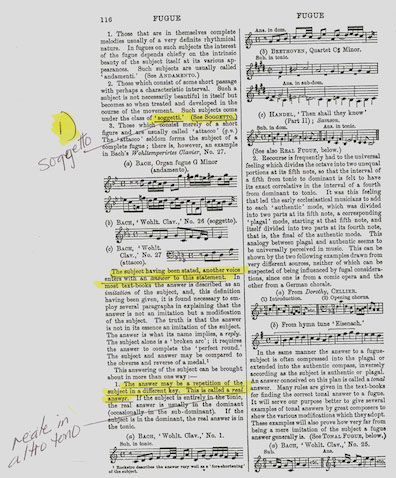

from superficial impressionistic reading of an article by

Ralph Vaughan Williams in the second edition of Grove's

Encyclopedia of Music, published from 1904 to 1910. On

the inside cover of a copybook Joyce listed, in Italian, eight

elements of a "Fuga per canonem"—terms like "subject,"

"answer," and "countersubject"—that he apparently intended to

graft onto the chapter that he had begun working on.

Joyce was a magpie and a skimmer of texts, but when dealing

with things like literature and philosophy he had an uncanny

facility for pulling out details that would establish a rich

intertextual dialogue with his own writing. Brown argues that

his engagement with the Grove encyclopedia entry, by contrast,

represents "pure cribbing." "Fuga per canonem" reflects his

misunderstanding of Vaughan Williams's observations early in

the article (on the first page reproduced here) that "a form

which has inspired the most magnificent music of the greatest

composers" (i.e., works by Bach and others) began much more

simply: "In the 16th century the word meant a movement in

canonic form; indeed the name 'canon' is merely short for

'fuga per canonem', a fugue according to rule." Some people in

that era practiced the "limited fugue" or "strict

canon"—simple rounds of the Frère Jacques variety.

Others played with freer forms that ultimately led to the

splendid complexity of the Baroque era. Joyce got it exactly

backwards, then: canonem refers to the simple

precursors from which fugues later evolved, not to a

hyper-complicated structure.

Brown attempts to puzzle out what Joyce wrote down about the

eight elements of a complicated fugue and what he meant by

them. Her specific findings do not bear repeating here, but

her assessment of their overall significance does. Vaughan

Williams, she notes, was describing possible elements

that a fugue might feature, not "regular parts," and Joyce

grasped very little of their complex musical significance. His

purported mastery of fugue theory was "bogus to none," and he

used the terms he cribbed from Grove's as "an

inspiration—not a template" to start playing with language in

new ways in Sirens. Even his reference to a quintet in

Die Meistersinger appears to come from the same essay

in the encyclopedia. None of this means that he was not

thinking of his eight terms as he introduced different

characters and themes into his chapter—probably he was—but it

does mean that readers need not search for some fiendishly

intricate theory to make sense of the verbal patternings in Sirens.

Probably only one structure in Sirens could not have

been conceived without the example of a musical structure. The

chapter begins with a list of verbal motifs divorced

from any narrative framework. After nearly five dozen

fragmentary non-paragraphs, ending with "Done," someone says,

"Begin!" and a recognizable narrative commences. All of these

clusters of words eventually appear in the narrative, and much

of the pleasure of reading it consists in retrospectively

learning what events they reference. This structure may well

be unprecedented in literature, but every operagoer will

recognize what is happening. Operas often begin with an

instrumental overture in which musical themes that will appear

later in the work's arias, duets, and choruses sound before

anything happens on stage. People who already know the work

can take pleasure in being reminded of what is to come. People

who are new to it can be introduced to themes that they will

soon hear developed more fully.

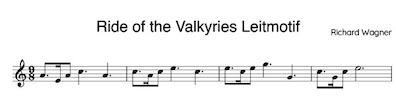

Mozart, Rossini, Bizet, and Verdi all practiced this kind of

musical foreshadowing, but the composer through whose writing

it gained a technical name (though he did not himself use the

term) was Wagner—the artist of whom Joyce spoke to Borach and

Weiss. The Wagnerian leitmotif is a melodic theme

that, instead of belonging to one musical number, becomes

recurrently associated with a character, situation, object, or

idea. Some even recur throughout the Ring cycle. Sirens

develops very comparable aural motifs associated with

characters, objects, and states of mind. Every careful reader

learns to recognize and enjoy the "tap tap tap" of the blind

piano tuner's cane, the "jingle" of Boylan's carriage bells,

the "blue" notes of Bloom's sadness, the "chips" of Simon's

fingernails, the "black deepsounding chords" of The Croppy

Boy, the distinctive rumblings of Bloom's intestines.

These are real aesthetic accomplishments of the chapter, not

mere pretensions to parity with great musicians. A few

ingenious critics may affect to hear the play of fugal

subjects and countersubjects in various sentences, but every

attentive reader will quickly learn to recognize these simple

aural themes and appreciate the lovely music that Joyce makes

from them.

Both schemas

list the Art of Sirens, unsurprisingly, as Music, and

its bodily Organ as the Ear. The Gilbert schema lists the

Symbol as Barmaids, and the Linati schema lists the Sense

(Meaning) as The Sweet Deception.