Banba

Parody. "He is gone from mortal haunts: O'Dignam,

sun of our morning. Fleet was his foot on the bracken: Patrick

of the beamy brow. Wail, Banba, with your wind: and wail, O

ocean, with your whirlwind": immediately after his send-up of

Theosophy Joyce appends another riff on the funeral theme,

this one alluding to ancient bardic legends about the

pre-Christian gods. The goddess Banba was well known to

contemporary enthusiasts for Celtic mythology. Like her more

famous sister Erin, who is shown here surrounded by winds and

oceanic waters, she personifies Ireland. Unlike other

parodies, this one seems to be commenting on what comes after

it: Bob Doran's praises of the dear departed. The usual

procedure is not completely abandoned, however, because after

many paragraphs devoted to that conversation the Banba voice

briefly returns. This encore appears to echo language in

MacPherson's Poems of Ossian, suggesting that Scottish

as well as Irish sources are implicated in Joyce's mockery of

the fad for Gaelic antiquity.

Joyce could have encountered references to Banba in various 19th century Irish writers. One was James Clarence Mangan, whose poems he devoured as a young man and whom he praised extravagantly in an early essay. He must have known the Lament for Banba, which mourns Ireland's "bondage" as a death:

O my land! O my love!The language here is very different from the sentences in Cyclops, but one or two details suggest possible connections. Mangan mourns the death of Banba while Joyce has her mourn the death of Dignam. Mangan mentions Ulster's great O'Neill clans and Munster's O'Brien dynasty, while Joyce evokes the Gaelic past by mock-heroically transforming Paddy into the noble "O'Dignam." While he does not attempt anything like an imitation of the Lament for Banba, it seems possible that he was thinking of it.

What a woe, and how deep,

Is thy death to my long-mourning soul!....

Other lands have their chiefs,

Have their kings, thou alone

Art a wife, yet a widow withal!

Alas, alas, and alas!

For the once proud people of Banba.

The high house of O'Neill

Is gone down to the dust,

The O'Brien is clanless and banned....

His imagination might also have been stimulated by reading scholarly studies of the ancient legends. Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner note that Standish O'Grady, an Irish historian whom he seems to have consulted when writing about Cuchulainn, liked to refer to Ireland as Banba. The annotators observe that in The History of Ireland (1881) O'Grady wrote, "A writer of to-day will employ Erin where the bards used Banba" (174). It is not difficult to imagine Joyce encountering a sentence like that and spinning out of his teeming linguistic brain some lines that sounded bardic.

Nowhere else in Cyclops does one parodic aside

immediately follow another. That Joyce chose to do so here

suggests that, after exploring Theosophical ideas of an afterlife in which the human

spirit prepares for reincarnation,

he had more to say about non-Christian eschatology. Dignam is

now said to be, not exactly dead, but "gone from mortal

haunts," evoking the ancient Celtic idea of an

Otherworld. According to a popular belief that has persisted

through many centuries of Christian teaching, after the

Milesians conquered Ireland the Tuatha Dé Danann went

underground and became known by the term for earthen mounds, sidhe.

Their descendants, the "fairies" known as sidhe or aos

sí (pronounced SHEE) dwell in Tir na nÓg, the

Land of the Young, and legends say that some human beings have

visited that place in which time stands still. Perhaps Paddy,

like Oisín, has left

"mortal haunts" for immortal ones.

One more irregularity follows. Some dialogue about Paddy

Dignam's death succeeds the parody, concluding in Bob Doran's

slobbering drunken praises of "The finest man," "the finest

purest character," "The noblest, the truest." This talk is the

object of the parodic mockery, and a brief reprise of the

Banba language follows it: "And mournful and with a heavy

heart he bewept the extinction of that beam of heaven."

Clearly this is the same voice that praised Dignam as the "sun

of our morning," "Patrick of the beamy brow," but that parodic

voice has been absent for quite a while. Joyce pulled the same

trick while singing the praises

of the produce markets, but in that instance only a

short two-sentence paragraph interrupted the interruptive

parody. Here seventeen such paragraphs of conversation

intervene.

Slote and his colleagues note that the language in this part

of the parody resembles a sentence in Hugh Blair's

late 18th century "Critical Dissertation" to the Poems of

Ossian: "But the poet's art is not yet exhausted. The

fall of this noble young warrior, or, in Ossian's style, the

extinction of this beam of heaven, could not be rendered

too interesting and affected." Ossian (Oisín) is a legendary

Irish bard, the son of Finn McCool, but in the 1760s Scottish

poet James MacPherson claimed to have collected and translated

a cycle of his heroic poems that had been kept alive in the

Scottish Gaelic oral tradition. The poems were probably a

hoax, composed by MacPherson himself, but they gained

international renown in the 19th century and sparked interest

in the revival of Gaelic language and culture in Ireland at

the end of the century, helping return Oisín to his native

land. Joyce's parodic mockery of Irish Literary Revival tropes

here probably reflects awareness of this pan-Gaelic ping-pong

and the alleged fraudulence of MacPherson's famous

translations.

The Harp of Erin, 1867 oil on canvas painting by Thomas

Buchanan Read held in the Cincinnati Art Museum. Source:

Wikimedia Commons.

The Tuatha Dé Danann represented in Riders of the Sidhe, 1911

tempera on canvas painting by John Duncan held in the Dundee

Art Galleries and Museums. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

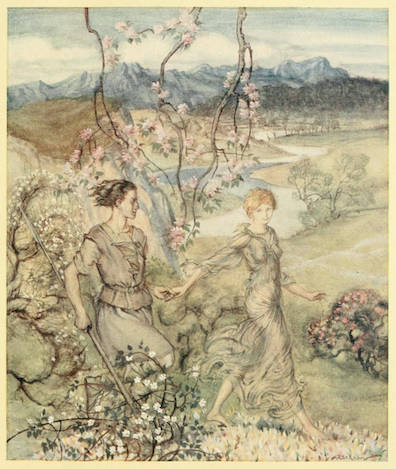

Arthur Rackham's Land of the Ever Young, an illustration in

Irish Fairy Tales (1920). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ossian Singing His Swan Song, 1780s oil on canvas painting by

Nicholai Abildgaard, held in the Statens Museum for Kunst,

Copenhagen. Source: Wikimedia Commons.