Distinguished

scientist

Parody. "The distinguished scientist Herr

Professor Luitpold Blumenduft tendered medical evidence

[...] a morbid upwards and outwards philoprogenitive

erection in articulo mortis per diminutionem

capitis": when Joe Hynes jokes that the erections

of hanged men bear out the saying "Ruling passion strong in

death," the bar's visiting amateur scientist feels compelled

to point out that there may be a purely physiological

explanation for the "phenomenon," and this parodic paragraph

makes fun of Bloom for presuming to speak with medical

authority on the subject. Mockery of Hibernophilia drops away

here, as befits the first parodic interruption to turn from

Things Irish to the Unwelcome Outsider. Now the focus is on

German Jewish doctors.

This is the cultural context in which Bloom, aka Henry Flower, is transformed into "Herr Professor" (the German title for full professors) "Luitpold" (Leopold) "Blumenduft" (Flower-Scent).

The address mocks him for pretending to medical knowledge far above his head (he has not even attended university and struggles to remember his high school science lessons, though his instincts are often good) by endowing him with the most elite academic honorific (not all researchers earn the title of Professor, and it outranks mere Doktor in the German hierarchy). Simultaneously, the German appellation manages to suggest that Bloom is a foreign Jew who does not belong in Ireland (his father, like Flexner's, emigrated from the continent). When the Nazis rose to power in the 1930s, many of Germany's accomplished Jewish ProfessorDoktors likewise fled their native land.

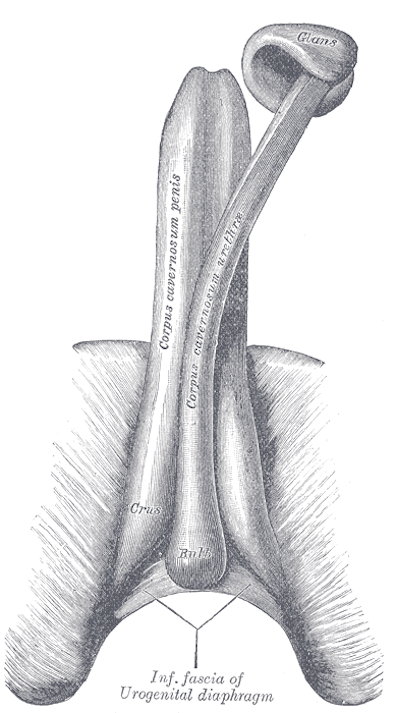

Professor Blumenduft testifies that hanging would cause "the instantaneous fracture of the cervical vertebrae and consequent scission of the spinal cord." Severing the spinal cord causes death, but it could also produce "a violent ganglionic stimulus of the nerve centres of the genital apparatus." Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner cite an authority quoted in Jeffrey Meyers's "Erotic Hangings in Cyclops," JJQ 34 (1997), psychiatrist H. L. P. Resnik: "The lumbar cord reflex center, which mediates both erection and ejaculation, is under the influence of [...] the cerebral cortex. This would explain erections immediately following a hanging when inhibitory impulses have been suddenly severed." Removing those inhibitions causes "the elastic pores of the corpora cavernosa to rapidly dilate in such a way as to instantaneously facilitate the flow of blood to that part of the human anatomy known as the penis or male organ." The corpora cavernosa are expandable erectile cylinders running the length of the penis that fill with blood during sexual excitement.

Doctors like to use terms derived from Latin and Greek, so the parody concludes with a formidable string of Latin and Greek words. Bloom's "jawbreakers about phenomenon and science and this phenomenon and the other phenomenon" are mocked by Professor Blumenduft's pretentious reference to a "phenomenon which has been denominated by the faculty a morbid upwards and outwards philoprogenitive erection in articulo mortis per diminutionem capitis." Presumably the "faculty" in question is the university community of which the esteemed professor is a member. These scientists do not name phenomena, rather they denominate them. The phenomenon in question, the one that causes penises to move "upwards and outwards," is "morbid" because it occurs in the process of dying, but it nevertheless can be called "philoprogenitive," loving the production of offspring. (Perhaps, then, Joe Hynes is right after all in supposing that the ruling passion is strong in death!)

In articulo mortis per diminutionem capitis means "At the point of death through lessening of the head." But as Slote and his colleagues point out, diminutionem capitis can also mean "forfeiture of civil rights" (Julius Caesar uses the phrase in this way). So a man who has lost his civil rights after trial by a jury of his peers may be hung by the neck until dead, causing a diminution of his cervical head but an enlargement of his penile one. Here readers get a glimpse of the manically precise employment of classical words that awaits them in Ithaca.

Photographic portrait of Abraham Flexner in The World's

Work, vol. 20 (1910). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The two corpora cavernosa of the penis (only one is

labeled) and the singe corpus cavernosum of the urethra,

isolated in an anatomical drawing by Henry Vandyke Carter

published in Henry Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body (1918).

Source: Wikimedia Commons.