Royal

Irish Constabulary

Among those in attendance at an execution, according to a Cyclops

parody, are "Big strong men, officers of the peace and

genial giants of the royal Irish constabulary." For readers

attentive to grammar but ignorant of antiquated Irish policing

structures, the word "and" in this sentence presents a puzzle.

Joyce uses the British word for policemen, "constable," in

many chapters (Calypso, Lestrygonians, Wandering Rocks,

Cyclops, Circe, Eumaeus). Should one infer,

then, that "officers of the peace" refers to members of the

"constabulary," and that "genial giants" tautologically

renames them? Or do these two noun phrases refer to two groups

of "Big strong men," only one of them members of the

"constabulary"? The second reading makes better sense: the

peace officers are probably policemen, but the genial giants

are certainly members of the Royal Irish Constabulary, a

quasi-military outfit. Only in Cyclops does the novel

refer to this organization by name, though it appears that Jack Power works in its

Dublin Castle headquarters.

Although it performed some routine policing and enforced various bureaucratic laws, the RIC's main charge was suppressing rebellions and other violent uprisings. It used lethal force in the Tithe War of the 1830s, the Young Irelander Rebellion of the late 1840s, the Fenian Rising of the 1860s, the Land War that began in 1879, and the revolutionary ferment following the 1916 Easter Rising. In 1920-21, when material for uniforms ran low, new recruits, many of them ex-military, were given khaki military trousers to go with their dark green tunics. Known as the "Black and Tans" because of this mismatched dress, they became notorious for murder, arson, looting, and reprisal attacks (some admittedly prompted by IRA soldiers shooting their colleagues in the back on dark country roads).

This history no doubt made the RIC unpopular with Irish nationalists, which may account for its being mentioned in the ardently nationalist confines of Barney Kiernan's pub. When the Citizen's dog is first introduced the narrator remarks, "I’m told for a fact he ate a good part of the breeches off a constabulary man in Santry that came round one time with a blue paper about a licence." The mention of more constabulary men in the execution parody suggests that Dubliners too felt threatened by the RIC. Although its remit did not include Dublin, it was run out of Dublin Castle, the administrative center of British state power in Ireland. Many of its troops were billeted in barracks around the city, and they could be called upon to suppress dangerous dissent anywhere in Ireland, the capital included. Why are some of these troops attending the execution of a political dissident? The parody adopts the upbeat and sentimental, voice of a newspaper article:

the vast concourse of people, touched to the inmost core, broke into heartrending sobs, not the least affected being the aged prebendary himself. Big strong men, officers of the peace and genial giants of the royal Irish constabulary, were making frank use of their handkerchiefs and it is safe to say that there was not a dry eye in that record assemblage.Of course this is rank fiction. If RIC constables had in fact attended such an event, their job would have been to fire on any onlookers who reacted violently to the spectacle. Glossing a reference to "buckshot" in another of the Cyclops parodies, Gifford suggests that "it may recall those Irish 'martyrs' who benefited from William E. ('Buckshot') Forster's determination that the Royal Irish Constabulary (for humanitarian reasons) should use buckshot rather than ball cartridges when firing on crowds. Forster (1819-86) was chief secretary for Ireland (1880-82) and a Quaker."

1867 RIC badge, rendered in a 2019 digital image by

Cyberbeagle. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Undated photograph of RIC men, held in the Imperial War

Museum, London. Source: www.neversuchinnocence.com.

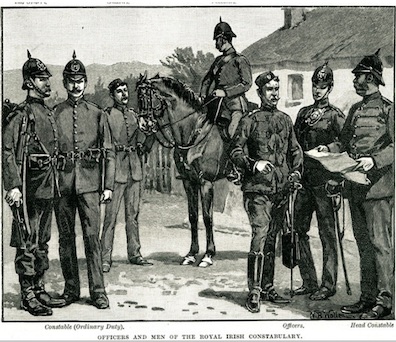

Different kinds of uniforms worn by RIC constables. Source:

www.facebook.com.

Undated photograph, possibly ca. 1919-20, of RIC constables,

possibly on their way to guard Dublin Castle. Source:

www.facebook.com.

RIC troops on rural patrol duty ca. 1889. Source:

www.facebook.com.

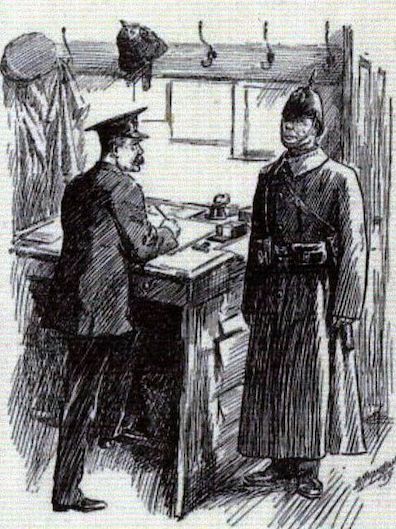

RIC recruit reporting for duty at a Dublin barracks. Source:

www.facebook.com.