Book 5 of Homer's poem tells how Odysseus, who has gained his

release from Calypso's island, sails for many days and then is

shipwrecked by Poseidon. He washes up on an unknown beach

battered, exhausted, and naked, crawls under some bushes, and

falls asleep. Book 6 tells how, the next morning, the lovely

young princess of the Phaeacians who rule this island drives a

wagon loaded with clothes down to the water to wash them,

because she hopes to find a husband and must look her best.

She and her slaves do the laundry, bathe, rub oil into their

bodies, eat, and then throw a ball to each other. Nausicaa is

good at the play, but one of her companions fails to catch the

ball, which rolls into an eddy. Odysseus is waked by the sound

of women shrieking. He emerges naked, covered only with a

leafy branch, to the terror of the slave girls, but Nausicaa

stands her ground.

He wondered, should he touch her knees, or keep

some distance and use charming words, to beg

the pretty girl to show him to the town,

and give him clothes. At last he thought it best

to keep some distance and use words to beg her.

The girl might be alarmed at being touched.

His words were calculated flattery.

(6.142-48, trans. Wilson)

Addressing the young woman as if she might be a goddess, he

says, "that man will be luckiest by far, / who takes you home

with dowry, as his bride. / I have seen no one like you. Never,

no one. My eyes are dazzled when I look at you" (158-61).

Relating his ordeal, he begs her to give him some clothes and

show him the way to town: "So may the gods grant all your

heart's desires, / a home and husband, somebody like-minded"

(181-81). Nausicaa agrees, and after Odysseus washes the salt

from his hair and rubs his skin with oil, Athena makes him too

appear godlike: "his handsomeness was dazzling. The girl was

shocked.... Before, he looked so poor and unrefined; / now he is

like a god that lives in heaven. I hope I get a man like this as

husband" (238-39, 243-45). She tells him how to get to her

father's house but declines to accompany him, because people

would talk: "So they will shame me. I myself would blame / a

girl who got too intimate with men / before her marriage"

(284-86).

Joyce mimics every major element of this scene. Like

Nausicaa, Gerty MacDowell (for that is the maiden's name, dear

reader) prides herself on her clothes and longs to be married.

She goes to the seaside with some female companions to whom

she feels superior, not to wash clothes but to tend children.

The boys play with a ball and it finds its way to Bloom. He

throws it back and it lands at the feet of Gerty, who (less

athletic than Nausicaa, for reasons revealed later) attempts

to kick it back to the boys but misses. The interaction draws

her attention to the man, and his sad face moves her. Sounds

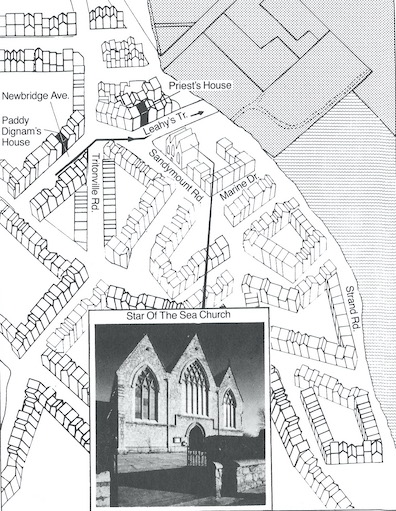

waft out of the Star of the Sea church, imploring the protectress of sailors, and as

the gazing progresses the foreigner's sad face becomes

phenomenally handsome, "the image of the photo she had of

Martin Harvey, the matinee idol."

All of these actions have clear analogues in the Odyssey.

Somewhat less obvious are the ways that Joyce responds to the

differing perspectives of a young woman and a more experienced

older man in Homer's poem. Nausicaa thinks she may have found

a husband, but Odysseus is only using "calculated flattery" to

effect a rescue. Similarly, Gerty decides that this is her

"dreamhusband" and quickly allows herself to develop fantasies

of a married life with him, but Bloom takes advantage of the

romantic transport to gratify needs more immediate and less

lasting than matrimony. Nausicaa is attracted to the stranger

but also cautious. Gerty more brazenly skirts the limits of

maiden modesty, allowing Bloom to feast his eyes on her but

feeling that "He was eying her as a snake eyes its prey. Her

woman's instinct told her that she had raised the devil in

him." Homer's inspired idea of introducing a naked man into a

group of young women finds hilarious new expressions in Nausicaa.

When Cissy goes over to Bloom to ask him for the time, "she

could see him take his hand out of his pocket, getting

nervous." Gerty sees him as "a man of inflexible honour to his

fingertips. His hands and face were working."

Joyce critics seldom notice how extensively Nausicaa

echoes Homer's action, probably because the echoes of a more

obvious literary model tend to drown it out. By the technique

of free indirect narration

used elsewhere to foreground the sensibilities of Bloom and

Stephen, more than half of this chapter hovers close to

Gerty's thoughts, parodying the style of books that a woman

like her would read. Romance novels of the 19th century tended

to privilege feeling over thought, frequently making a

positive virtue of sentimentality. Joyce's prose here, an

extension of the parodic principle introduced in Cyclops,

is a master class in cloying sentimentality, preciosity,

cliché, confessional intimacy, and beauty tips. In a 1920

letter to his friend Frank Budgen, Joyce said that it is

"written in a namby-pamby jammy marmalady drawersy (alto là!)

style with effects of incense, mariolatry, masturbation,

stewed cockles, painter's palette, chitchat, circumlocutions,

etc., etc."

He chose one work in particular to mock. American writer

Maria Cummins's novel The Lamplighter (1854) was

immensely popular: in the first five months it sold more than

65,000 copies, and there were numerous subsequent editions. It

tells the story of Gerty Flint, an impoverished young woman

who undergoes a moral education, becomes a model of pious

self-sacrifice, and is rewarded with marriage and money.

Gifford offers a succinct plot summary: Gerty "begins life

'neglected and abused...a little outcast', sweet, as expected,

but vengeful and vindictive, capable of 'exhibiting a very hot

temper'. She rapidly comes into possession of 'complete

self-control' and then of a sentimental religiosity that,

combined with considerable coincidence, rewards her with the

good life of self-sacrifice (and of affluence in her marriage

to Willie, the love of her childhood, who has himself made it

from rags to riches)." The model of the parody is acknowledged

when Gerty thinks of having "that book The Lamplighter

by Miss Cummins, author of Mabel Vaughan and other

tales." (Mabel Vaughan, another novel, was published in

1857.)

Like the Gerty of The Lamplighter, Gerty MacDowell is

pious. She comes from a lower-middle-class family where money

is tight, but she dresses elegantly and considers herself born

for better things: "Had kind fate but willed her to be born a

gentlewoman of high degree in her own right and had she only

received the benefit of a good education Gerty MacDowell might

easily have held her own beside any lady in the land and have

seen herself exquisitely gowned with jewels on her brow and

patrician suitors at her feet vying with one another to pay

their devoirs to her." She dreams of marrying her childhood

love Reggy Wylie (the name recalls Gerty Flint's Willie),

whose family is Protestant and better-off, and she imagines

how she will be regarded when they are married: "in the

fashionable intelligence Mrs Gertrude Wylie was wearing a

sumptuous confection of grey trimmed with expensive blue fox."

Gerty also inherits some of her namesake's nasty pettiness.

She entertains catty rivalrous thoughts about her friends. Edy

Boardman, who is inclined to make fun of her (pure jealousy,

in Gerty's view), is "squinty Edy," an "Irritable little

gnat," "puny little Edy." She prides herself on being "very petite

but she never had a foot like Gerty MacDowell, a five." The

highspirited and humorous Cissy Caffrey offers no offense but

still comes in for some scorn. Gerty watches her "tossing her

hair behind her which had a good enough colour if there had

been more of it." Energetically wrangling two small boys on

the sand, she becomes unladylike, "the flimsy blouse she

bought only a fortnight before like a rag on her back and a

bit of her petticoat hanging like a caricature." Nor does

Gerty feel tender toward the children: "Little monkeys common

as ditchwater. Someone ought to take them and give them a good

hiding for themselves to keep them in their places, the both

of them."

While she does not (yet) have much Christian kindness, Gerty

MacDowell does have a strong instinct for heterosexual

flirtation. Nothing in the narrative shows that she feels the

kind of frankly lustful desires that compel Bloom to spank the

monkey in his pants, and she protects herself against such

desire by imagining that men are brutes and women victims.

Nevertheless, she manifests unconscious complicity in his

lustful fantasy by leaning far back in a posture that not only

shows him her underwear but also mimes a sexual swoon. Both

Gerty's unspoken aggression and her unacted sexuality make her

an immature version of the Molly of Penelope, and for

both her and Bloom the seaside gazing feels like a precursor

to a real sexual relationship, however unlikely that may be.

Joyce here takes one final cue from Homer, whose hero is a

married man trying to get back to his wife but who is not

averse to some opportune flirtation. For Bloom the object is

not gaining an introduction to the king of Scheria, but

finding some relief from his present defeated condition:

"Goodbye, dear. Thanks. Made me feel so young."

As for the question of why he is on this beach in the first

place, that is slowly answered as the chapter proceeds. At

several points Gerty mentions "Mr Dignam and Mrs and Patsy and

Freddy Dignam," whose Sandymount house is quite nearby, and

Bloom later thinks of "coming out of Dignam's." Still later he

thinks, "Off colour after Kiernan's, Dignam's. For this relief

much thanks." Cyclops showed him going to Barney

Kiernan's pub to meet Martin Cunningham about the collection

for Dignam's widow, and now it becomes clear that they have

paid her a visit. Confrontations with a violent nationalist in

a dark pub and a grieving widow in a house of mourning have

left him "Off colour," and sexual satisfaction goes a long way

toward restoring his peace of mind.

Cyclops ends at about 6 PM and Nausicaa begins

at about 8. Although some distance separates the pub near

Capel Street and the house in Sandymount, traversing it would

take nothing like two hours. Much of this time must have been

spent in the Dignams' house, but Joyce chooses not to

represent the scene. In a novel structured around successive

hours of one day, why might he have chosen to create this

two-hour gap? Various explanations seem possible, but Don

Gifford's may be the best: true acts of charity do not call

attention to themselves. According to Matthew 6:3, the right

hand should not know what the left is doing. Bloom does not

come off altogether well from the narration in Nausicaa,

but an action that is not narrated goes some way toward

balancing the account.