Joyce conceived his final chapter not as a reunion of husband

and wife—that happens in Ithaca—but as a long

soliloquy serving as a kind of coda to the novel's action.

"Penelope," whose Technic one schema calls

"Monologue (female)," goes Proteus—"Monologue

(male)"—one better, by eliminating narrative entirely. Lying

awake in the dark, Molly weaves an ever-changing mix of

memories, expectations, judgments, questions, and desires,

perhaps in sympathy with the endless weaving and unweaving of

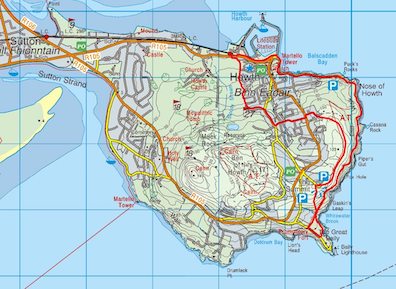

Homer's Penelope. The location is precise and unchanging—she

leaves her bed just once, to sit on the chamberpot next to

it—but her thoughts roam throughout Dublin and Gibraltar and

famously end on Howth Head. The time is more or less

knowable—after 2 or 3 AM, not yet dawn—but in Molly's mind

time seems barely to exist. Gilbert's schema lists no Hour for

the chapter, while Linati's gives the mathematical symbol of

infinity: ∞. Present consciousness is all there is, treating

the distant past as if it were yesterday. Grammar too seems to

violate boundaries, as the text unfurls in eight long

unpunctuated blocks and one must labor to decide where one

syntactic cluster ends and another begins, or to whom the

pronoun "he" may refer at any given moment. But the impression

of syntactic strangeness disappears when the words are read

aloud. Molly's is the language of ordinary speech, with one

recurring touchstone: the affirmative word "Yes."

In book 23 of the Odyssey, Penelope's nurse Eurycleia

gleefully rouses her from sleep with the news that her husband

has returned and slaughtered all the suitors. Penelope is

doubtful, then overjoyed, then suspicious again. She goes

downstairs and regards the bedraggled stranger uncertainly,

and when Telemachus berates her for being hardhearted she

tells him, "we have our ways to recognize each other, /

through secret signs known only to us two" (108-9, trans.

Wilson). A test follows, as Penelope directs Eurycleia to pull

the bed out of their bedroom and make it up for the stranger.

Odysseus is enraged, because he made one of the bed's posts

from the trunk of an olive tree, still rooted in the ground.

Who has dared to hack into it? Since this secret was confided

to only one servant, Penelope knows the man must be her

husband, and the couple embrace. "They would have wept until

the rosy Dawn / began to touch the sky, but shining-eyed /

Athena intervened. She held night back" (242-44). In this

magically extended gap of time the long-separated partners

make love, tell each other their stories, and at last sleep.

Joyce's version seems as different as could be. After

nestling his face in his wife's buttocks, the cuckolded Bloom

drops off into weary slumber head-to-foot in their rickety

brass bed, with nary a thought of violent retribution. The

wife is not a paragon of chaste fidelity but an

unapologetically lusty adulteress who regards her spouse with

longsuffering, scathing bemusement. Nevertheless, a kind of

testing is taking place, as interrogation of Bloom's flaws is

balanced against appreciation of his virtues. By the end of

the chapter it feels as if a tipping point has been passed.

Molly thinks about how she might get Bloom to perform his

sexual obligations again, and her monologue concludes with a

rapturous memory of him kissing her and proposing marriage.

The tidal swing in her emotions does appear to have an

analogue in the tough-minded withholding of affection followed

by joyous affirmation found in Homer's poem. And the

unpunctuated text does make it seem as if time has been

strangely lengthened and suspended.

In terms of imagery, Joyce did nothing with Homer's olive

tree—a symbol of deeply rooted, long-enduring partnership.—but

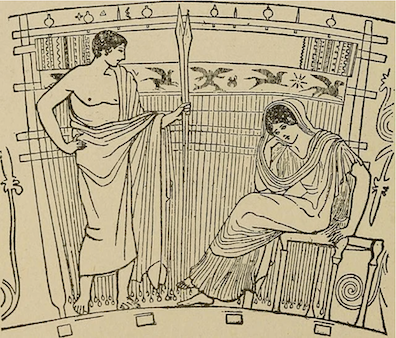

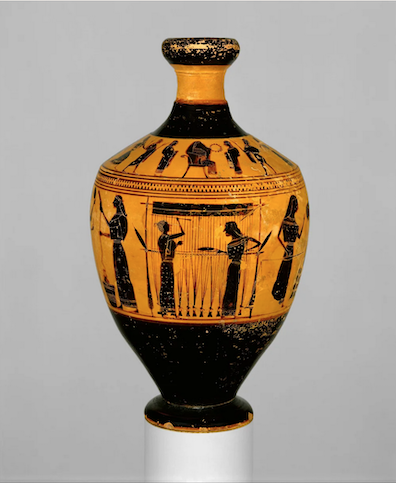

he seems to have responded to Penelope's weaving. Antinous

recounts how she argued that before marrying she must make a

fine funeral shroud for her father-in-law Laertes: "And her

words made sense to us. / So every day she wove the mighty

cloth, / and then at night by torchlight, she unwove it. / For

three long years her trick beguiled the Greeks" (2.105-8). As

with Scheherazade's tale, the shroud remains unfinished, male

expectations are thwarted, and time is lengthened. This image

may lurk behind the seeming endlessness of Molly's monologue

and her perpetually revised opinions. Joyce suggested another

symbolic image in the Correspondences to the Gilbert schema:

"Penelope" corresponds to "Earth," he wrote, and her "Web" to

"Movement." In a letter he wrote that the final chapter "turns

like the great earthball slowly and surely and evenly round

and round spinning." Evidently he was toying with the idea

from the end of Ithaca that Molly resembles an

Earth-Mother, the Greek-Roman "Gea-Tellus." The image of a

globe perpetually moving but always returning to the same

point feels consistent with the weaving and unweaving of a

tapestry.

Joyce called the eight enormous chunks of text "sentences,"

and if this were grammatically accurate they would surpass the

most egregious instances in Faulkner's novels. But Molly's

words actually break down into discrete sentences of no great

length. It is often difficult to know where one ends and the

next begins, but reading the chapter aloud forces one to

decide. The impression of nearly endless sentences is in fact

an illusion. In writing Aeolus Joyce took an

uninterrupted succession of narrative incidents and created an

impression of discrete units by inserting newspaper-like

headlines throughout the text. In Penelope he worked

in an opposite way and deleted the punctuation marks one would

expect, including the apostrophes that can be seen in the

Rosenbach manuscript.

Derek Attridge has challenged the widespread notion that

Molly's monologue has a "flowing" quality. He notes that Joyce

himself never urged such an image on readers and speculates

that the impression derives mainly from the long sentences and

overriding of syntactic rules (Joyce Effects, 93-95).

In fact, though, Molly's "syntactic deviations are

characteristic of casual speech"; they are much less radical

than many in the interior monologues of Stephen and Bloom; and

her true sentences are far shorter than ones in Oxen of

the Sun, Cyclops, and Ithaca (96-98). As visual

readers "we take the uninterruptedness of print as a

conventionally sanctioned sign for an uninterruptedness of

thought" (100), but when the words are read aloud this

impression vanishes. Molly's thought-processes are simply

"those of someone unable to sleep after an extraordinary day

that has stirred memories and provoked desires; we would

expect such thoughts to be insistent, helter-skelter, widely

ranging, yet constantly circling around a few dominant

preoccupations" (100). Joyce's odd arrangement of words on the

page need not indicate unusual states of mind in his

character. After so many radical narrative experiments in the

second half of Ulysses, readers should know better

than to assume such a "naturalistic connection" (101).

Whether Molly's words should be heard as characteristically

female, and, if so, whether Joyce's representation of female

speech should be commended, are questions I will not take up,

but there can be little doubt that one impetus for his chapter

came from listening to women speak. Nora Barnacle provided one

model. Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner note another: "According

to Herbert Gorman, Molly's predilection for the word Yes

was inspired by Lillian Wallace, the wife of Richard Wallace,

an illustrator Joyce knew in Paris. One day, Joyce sat

listening as Mrs Wallace talked to a young painter at her

country house. 'The conversation was long-winded and dull and

as Joyce drowsily listened he heard his hostess continually

repeating the word "yes". She must have said it a hundred and

fifty times and in every possible nuance of voice. And

suddenly Joyce realized that he had found the motif word for

the end of Ulysses' (James Joyce, p. 281)."