Molly's reference

to "the side of the rock" might conceivably be taken as

referring to the eroded cliff walls near the English Margate,

but nothing in the novel suggests that she has ever been there.

Gifford assumes that her vision of male beauty came from her

early days in Gibraltar, and Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner agree

with him. Gifford says of the Margate Strand in Gibraltar, "At

specified hours it was a for-men-only bathing place; but there

was also a bandstand on the strand, and it was a place of public

resort on summer evenings." This dual use might account for a

young woman catching sight of naked men.

But the other Margate too had a reputation for daring displays.

It is the beach where

"Those

Lovely Seaside Girls" is set: "Down at Margate looking

very charming you are sure to meet / Those girls, dear girls,

those lovely seaside girls." The song describes young men gazing

on "silks and lace," and "bloomers smart," as girls parade in a

modish seaside style of dress that was more revealing than

street clothes, but the beach provided still better

opportunities for voyeurism: both men and women swam there, and

in close proximity. Victorian public opinion held that

"promiscuous bathing" was a great danger. Seaside resorts like

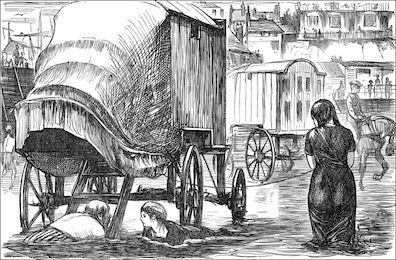

Margate provided horse-drawn "bathing machines" that enabled

people to enter fully clothed on the beach, change into their

swimwear while the vehicle was being pushed out into the waves,

and then modestly enter the water down some back steps that were

covered with fabric, giving swimmers some shelter from the sight

of people on the beach. At some resorts the men's and women's

bathing machines were kept far apart, but Margate apparently was

not one of them.

Not only were the bathing machines at Margate placed close

together, but evidently some men were in the habit of emerging

with no suits on. Mimi Matthews observes on her blog site,

mimimatthews.com, that some gentlemen "emerged from their

bathing machines in what the 2 September 1854 edition of

the

Leeds Times describes as an 'entirely

primitive state'. Once in the water, these naked gentlemen had

no compunction about approaching the female bathers nearby." The

chats and splashing contests that ensued attracted audiences on

the beach, "some of whom employed telescopes to get a better

view of the indecency. Of this 1854 incident, the reporter

noted that 'The beach was thronged with admiring spectators, and

many of them with glasses, although they were not required, as

the bathers, from the high tide, were close to the shore'.”

In the 1860s, "crowds at Margate" were still using telescopes

"to get a better view of the 'nude groups and sportive syrens'

in the water." A 23 July 1865 article in the

Era, a

London newspaper, reported that "these 'magnifying mediums' were

as likely to be used by ladies as by gentlemen." This was pretty

strong stuff in mid-Victorian England, and some saw it as a

threat to public morals. The writer of the article

observed, "There must be something morally infectious in the

atmosphere of this popular watering place that induces men and

women to do that at Margate which they would blush even to be

thought capable of doing in any other locality—namely,

disregarding all those social observances which are usually

called decency in men, and modesty in women.... The bathers of

both sexes romp, laugh, and perform all kinds of antics in which

the actual nudity of the men is infinitely less offensive to our

sense of decency than the modest immodesty of the clinging

gossamer vestment in which the females cover, without hiding,

their forms." This "chronic evil," the writer argued, corrupted

not only the bathers but also those watching from the sand.

In other parts of the UK, police actions were sometimes taken

against men who strayed within 200 yards of the spots reserved

for women. Such laws against promiscuous bathing were of a piece

with the obscenity laws that kept Joyce's works from being

published, and it seems likely that he took an interest in

Margate because it represented another form of resistance to the

enforcers of public morality. A transgressive exchange in

Circe

highlights the transcendent scandalousness of what Bloom, in

Eumaeus, calls "

Margate with mixed bathing." After

political candidate Bloom panders to his constituency by

promising "Free money, free rent, free love and a free lay

church in a free lay state," O'Madden Burke parries, "Free fox

in a free henroost." Bloom comes back with the still more

radical proposal of "Mixed races and mixed marriages," prompting

the comedian Lenehan to utter the crowning blasphemy: "

What

about mixed bathing?"