The chamberpot that the Blooms keep under their bed for

nighttime emergencies, and which Molly uses under just such

conditions at the end of the novel, is described as

"orangekeyed." This cryptic adjective probably refers to the

labyrinthine design sometimes called a Greek key, and various

details suggest that Joyce means it to evoke Homeric times.

Readers also learn in Calypso that the bedroom

contains a "broken commode," which Ithaca describes

more exactly as "A commode, one leg fractured, totally covered

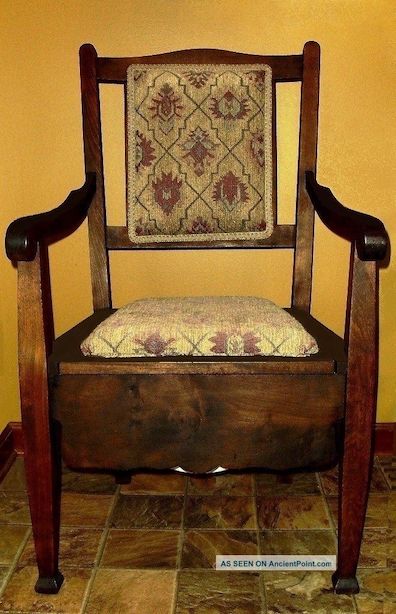

by square cretonne cutting, apple design." This is a wooden

chair, beautified by a fabric covering and concealing a

ceramic pot beneath its seat—a much more commodious appliance

for doing one's business. The commode long ago broke when

Molly was sitting on it, so the Blooms use the chamberpot,

purchased as one part of a matching set of ceramic items.

In Circe Bloom refers to "That antiquated commode.

It wasn’t her weight. She scaled just eleven stone nine. She

put on nine pounds after weaning. It was a crack and want of

glue. Eh? And that absurd orangekeyed utensil which

has only one handle." In Penelope Molly too recalls

breaking the commode. The realization that her period is

starting sends her looking for the pot: "wait O Jesus wait yes

that thing has come on me yes now wouldnt that afflict you...O

patience above its pouring out of me like the sea...I dont

want to ruin the clean sheets the clean linen I wore brought

it on too damn it damn it...wheres the chamber gone

easy Ive a holy horror of its breaking under me after that

old commode." Ithaca notes that the pot is one

part of a set: "Orangekeyed ware, bought of

Henry Price, basket, fancy goods, chinaware and ironmongery

manufacturer, 21, 22, 23 Moore

street, disposed irregularly on the washstand and floor

and consisting of basin, soapdish and brushtray (on the

washstand, together), pitcher and night article (on

the floor, separate)."

In his critical study Ulysses, Hugh Kenner argues

that "orangekeyed" must refer to an orange border in the kind

of continuous pattern called a key pattern, key meander, Greek

fret, or Greek key, implying multiple links to Homeric Greece.

The OED's first documented use of "key" as a kind of

graphic pattern "is dated 1876, in the first decade of Homeric

archaeology." The figure "characterised much Greek pottery of

the Geometric Period, the ninth to seventh centuries BC:

pottery of the lifetime (if he lived) of Homer" (144). Joyce

emphasizes the connection by coining his word in "the way

Homer formed many epithets, of which the most celebrated is rhododaktylos,

'rosyfingered,' by joining an attribute of colour or

brightness with a name." (Other such epithets include "wine-dark,"

"bronzed-armored," "grey-eyed"

or "shining-eyed," "white-armed," "red-haired,"

"flaming-haired," and "silver-footed.") Finally, although

Kenner does not mention it, much ancient Greek pottery was

thrown from iron-rich Attic clay and fired in oxygen-rich

environments that turned any unpainted surfaces intensely

orange. The 5th century cup shown here combines orange color,

a key pattern, and a woman using a chamberpot.

If this humble pot serving the Blooms' baser bodily needs is

meant to recall the Homeric age, the ironic audacity of the

connection would not have escaped Joyce's notice. In Telemachus

Mulligan says to Stephen, "The mockery of it!...

Your absurd name, an ancient Greek!" But Stephen's name

is far from meaningless:

both words contain ancient Greek meanings that figure in the

novel's symbolic structures. Soon Mulligan, who is well

schooled in Greek, is hearing Homeric echoes in his own name:

"My name is absurd too: Malachi Mulligan, two dactyls. But it has a Hellenic

ring, hasn't it? Tripping and sunny like the buck himself. We

must go to Athens." In these two instances, the word "absurd"

performs a kind of feint, suggesting that any hunt for

significance is illogical or inappropriate. When Bloom speaks

of "that absurd orangekeyed utensil" in Circe,

the adjective performs the same trick once more. Linking a

chamberpot to a great heroic era may seem discordant and

irrelevant, a mere mockery.

In fact it is a small arresting reminder that in human

experience some things stay eternally the same.