In Wandering Rocks Patsy Dignam stands gazing at a

poster that shows "two puckers stripped to their pelts and

putting up their props," announcing that "Myler Keogh,

Dublin’s pet lamb, will meet sergeantmajor Bennett, the

Portobello bruiser, for a purse of fifty sovereigns. Gob,

that'd be a good pucking match to see. Myler Keogh, that's the

chap sparring out to him with the green sash. Two bar

entrance, soldiers half price." Young Dignam dreams of going

to the fight, but then he looks more closely: "When is it? May

the twentysecond. Sure, the blooming thing is all over."

Other characters know about the fight and the role Blazes

played in it. In Cyclops Alf Bergan tells his

companions that Boylan turned the betting odds in his favor by

starting a false rumor that his man was drinking heavily: "He

let out that Myler was on the beer to run up the odds and he

swatting all the time." In Lestrygonians Nosey

Flynn reports the same story, noting that Boylan sequestered "the

little kipper down in the county Carlow...For near a

month, man, before it came off. Sucking duck eggs by God

till further orders. Keep him off the boose, see? O, by God,

Blazes is a hairy chap."

Myler Keogh was born in Donnybrook in 1867, the eldest son of

boxer and sawmill worker James "Clocker" Keogh. For five or

six years in the 1890s he was the middle-weight champion of

Ireland. Vivien Igoe says that his last fight was on 9 October

1903, but Frank McNally, in a 15 June 2021 Irish Times article,

suggests that it may have happened in 1904 when "Jem Roche of

Wexford knocked him out." Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner hold

that his career was over by 1904 but "Joyce evidently confused

him for another fighter with a similar name. The fight

mentioned here was the second round of a civil and military

tournament held at the Earlsfort Terrace Rink on 29 April

1904. This venue was frequently used for matches between

British soldiers and local civilian boxers. The civilian was

J. McKeogh, but his name was erroneously reported in the

press, with one variant being 'M. Keogh' (Freeman's

Journal, 29 Apr. 1904, p. 7, col. j), which probably

explains the confusion."

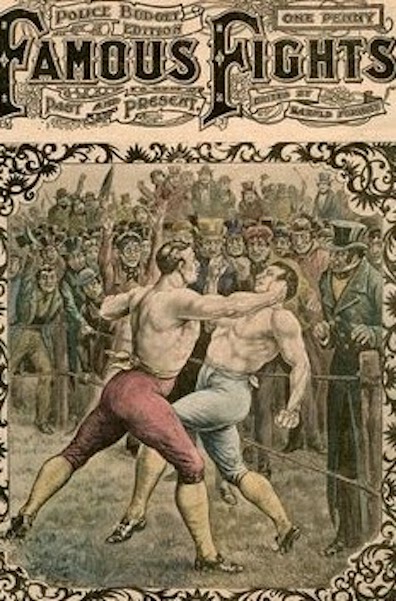

McKeogh did knock out his opponent, a private in the 6th

Dragoons named Garry, in the third and final round of this

match, so the report in Cyclops of a native son's

glorious victory over an Englishman is more or less accurate

even if Joyce got the wrong Keogh. But he took Garry out of

the story, replacing him with a British soldier named Percy

Bennett. Here Joyce was settling his own scores rather those

of his subjugated nation. The real Percy Bennett was an

English diplomat serving as consul-general in Zurich in 1917

when Joyce became involved in an embassy-supported project to

stage English-language plays. Colleagues knew him as "Pompous

Percy," Ellmann notes (425), and he was "annoyed with Joyce

for not having reported to the consulate officially to offer

his services in wartime, and was perhaps aware of Joyce's work

for the neutralist International Review of Feilbogen

and of his open indifference to the war's outcome" (423).

When Joyce fell out with consular worker Henry Carr, who

performed a role in The Importance of Being Earnest,

Bennett took Carr's side. Joyce retaliated by reducing him to

a "sergeantmajor" in the Portobello barracks and made Carr,

his subordinate, one of two drunken soldiers who assault

Stephen in Circe. Private Compton there warns Private

Carr, "Here, bugger off Harry. Or Bennett'll have you in the

lockup. Carr responds, "God fuck old Bennett. He’s a

whitearsed bugger. I don’t give a shit for him."

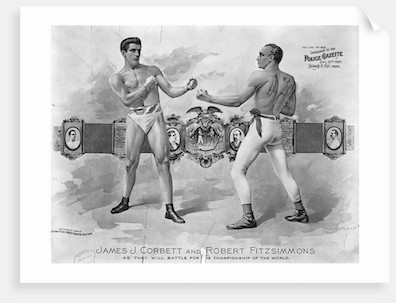

In a JJON essay, John Simpson observes that some 19th

century boxers adopted the ironic ring-name "lamb." One

English prize-fighter in particular, William Thompson, was

known by that name, perhaps because "His local support came

from a band of roughs known as the 'Nottingham Lambs'." "Pet,"

Simpson points out, is "one of the few high-profile English

words to derive from Gaelic." The phrase "pet lamb" came into

use in the 16th century to describe tame animals, and in the

19th century it became used in pugilistic circles to describe

a favorite boxer. Joyce evidences awareness of this trade

lingo in calling Keogh "Dublin's pet lamb," and

likewise in terming Bennett "the Portobello bruiser."

Simpson quotes newspaper references to the Bermondsey Bruiser

in 1859 and the Battersea Bruiser in 1905.