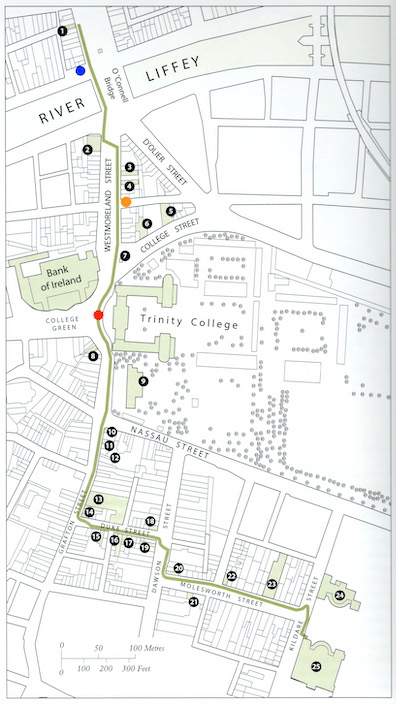

Lestrygonians starts with Bloom standing in front of "Graham

Lemon's," the Lemon

& Co. confectioner's shop at 49 O'Connell

(Sackville) Street Lower. After meditating on candy he walks

toward the river reading a "throwaway" that has been thrust

into his hand, past "Butler's monument house corner,"

which is called George Butler's "monument house, musical

instrument warehouse" in Thom's because it is located

across from the O'Connell

monument at the base of O'Connell Street. (Slote,

Mamigonian, and Turner observe that although this business was

the last house on the quay, it was not actually on the corner.

That honor belonged to 56 Lower O'Connell Street.) Bloom

glances down "Bachelor's walk," the quay on which

Butler's sits at number 34. At nearby number 25 he sees a

famished-looking Dilly Dedalus "there outside Dillon's

auctionrooms." In Wandering Rocks Dilly is still standing outside Joseph

Dillon's auction business, waiting patiently for her

improvident father to appear.

Bloom walks onto the "O'Connell bridge" and sees "a

puffball of smoke" rising from a Guinness brewery barge

passing underneath. He contemplates the vats of porter, the

sewage-laden waters of the Liffey, and the hungry gulls

flapping about, buys two cakes to feed the birds, and throws

away the throwaway. Having crossed the bridge, he looks up at

"the ballastoffice," a five-story building on the

corner of Aston's Quay and Westmoreland Street which housed

the offices of the Port of Dublin and held a very large and

accurate clock on its facade, as well as the large "timeball" on its roof

which makes him think of parallax.

He waits for a procession of sandwichboard bearers to pass by

him in the gutter, and then crosses "Westmoreland street when

apostrophe S had plodded by."

Walking along the sidewalk on the east side of the street, he

encounters Mrs. Breen and holds a long conversation with her.

As they talk, "Hot mockturtle vapour and steam of newbaked

jampuffs rolypoly poured out from Harrison's." This

business at 29 Westmoreland Street is listed as a

"confectioner's" in Thom's, like Lemon's, but it seems

to be a restaurant dedicated to baking and cooking rather than

candies. Bloom watches a street urchin breathing in the rich

aromas coming from its sidewalk grate to quell his hunger

pangs. Saying goodbye to Josie and moving on, he goes by "the

Irish Times" at number 31 and thinks of the

ads for a lady typist he has placed there.

At "Fleet street crossing," the midpoint of

Westmoreland Street, he thinks about where he should have

lunch—Rowe's? the Burton?—and then walks on "past Bolton's

Westmoreland house," a spirit grocer at numbers 35-36.

Soon he is at the end of Westmoreland Street, where the

imposing neoclassical building built to house the Irish

Parliament, and now owned by the

Bank of Ireland, begins its majestic semicircular wrap

around the north side of College Green: "Before the huge high

door of the Irish house of parliament a flock of

pigeons flew." Bloom thinks about pigeons voiding their bowels

on pedestrians: "Their little frolic after meals."

Then his attention is drawn in the opposite direction as "A

squad of constables debouched from College street,

marching Indian file." This street, which comes around the

northwest edge of Trinity College and joins Westmoreland

street from Bloom's left, held a police station and also the

M'Caughey Restaurant at numbers 3-4. The men's contented,

"Foodheated faces" tell Bloom that they have just finished

lunch, and he watches as "They split up into groups and

scattered, saluting towards their beats. Let out to graze." At

the same time, "A squad of others, marching irregularly,

rounded Trinity railings making for the station. Bound for

their troughs. Prepare to receive cavalry. Prepare to receive

soup." These policemen are marching northeast rather than

southwest, clearly comprising the next lunch shift.

Crossing College Street, Bloom walks "under Tommy Moore's

roguish finger." This freestanding bronze statue of

Irish poet Thomas Moore,

funded by public subscription, was erected in 1857 on a

granite base in a traffic island in the middle of the street.

Bloom thinks, "They did right to put him up over a urinal." He

is next seen walking where the second group of policemen had

been, by the iron railings that separate Trinity College's "surly front" from College Green.

This extremely busy intersection no longer has anything green

about it: "Trams passed one another, ingoing, outgoing,

clanging." Bloom contemplates the sheer numbers of human

beings packed into cities like sardines and concludes, "This

is the very worst hour of the day. Vitality. Dull, gloomy:

hate this hour. Feel as if I had been eaten and spewed."

A few steps more and he is passing the "Provost's house,"

a large and imposing stone pile that stands on the

southwestern corner of the campus. Bloom thinks, "The reverend

Dr Salmon: tinned salmon. Well tinned in there. Wouldn't live

in it if they paid me." Slote and his collaborators point out

that the Reverend George Salmon, D.D., Regius professor of

divinity, was indeed the Provost of Trinity College in 1904,

but only until his death on January 22. They cite Eric

Partridge as authority that "tinned" can mean wealthy, and

point out that Salmon earned over 1,000 pounds a year as

Provost. According to the 20 April 1904 Freeman's Journal,

at his death he left an estate valued at £27,200. Tinned

salmon, indeed. This reflection, and the surly grandeur of the

house, provide more grist for Bloom's existential nausea.

Looking to the right across the first block of Grafton

Street, he sees sunlight glinting from "the silverware

opposite in Walter Sexton's window." Walter Sexton was

listed in Thom's as a "goldsmith, jeweller,

silversmith, and watchmaker" at 118 Grafton Street. Bloom

contemplates John Howard Parnell passing by the shop window,

and then he becomes aware of George

Russell passing him on the east side of the street and

thinks of his vegetarianism. Crossing at the "Nassau street

corner," he stands in front of the Yeates and Son

optical shop on the south side of Nassau Street and looks back

at the roof of the Parliament building, testing his vision and

thinking disconsolately of astronomy.

From this point, almost exactly halfway through the chapter,

the character of the cityscape changes subtly but distinctly.

Bloom enters Grafton Street proper, bounded on both sides by

fancy shops. Grand monumental displays are left behind and

commerce prevails. There are more restaurants and pubs, more

businesses in which he is personally interested, and a more

confusing warren of streets. Bloom follows a much less direct

path as his feet take him south, then east, then briefly back

to the west, then east again, then south, then east, and,

finally and abruptly, south to the entrance of the National

Museum. Given Joyce's gastrointestinal conceit, one may wonder

whether the relatively straight shot that he has taken from

O'Connell Street to Grafton Street, passing through the busy

churning of College Green, is meant to correspond to the

relatively straight line from mouth to duodenum via the

stomach. If so, then the much curvier walk that follows should

be imagined as intestinal.

Such a reading may be thought overly ingenious (I do not know

if anyone has suggested it before) but the schemas show that Joyce was

thinking of "peristaltic" movement through the alimentary

canal, and there can be little doubt about where he saw that

motion concluding: after Lestrygonians ends, Bloom

goes into the National Museum to see whether the statue of a

Greek goddess possesses an anus. (Buck Mulligan reports this

detail in Scylla.) Once a reader realizes that Bloom's

feet trace question marks

in Lotus Eaters, anything seems possible.