In book 12 of the

Odyssey

Circe tells Odysseus that if he wants to avoid the

Wandering Rocks he will

have to sail through another tight rocky strait. On one side,

high in a cave on a towering cliff face, dwells a monster whose

six heads will devour six men. On the other lurks a whirlpool

big and violent enough to take down the entire ship. Later in

this book Odysseus does as Circe advises and sails close to the

cliff face. Scylla snatches six men from the ship and hauls them

screaming up to the cave, but the voyage continues.

Joyce's text alludes to this story in some passages that seem

more incidental than consequential. When Stephen is describing

Shakespeare's sexual jealousy he fancies that different passions

swirl in the poet's breast "and the two rages

commingle in a

whirlpool." It is hard to know what to make of this brief

reference. The whirlpool is a metaphor for maddening mental

obsessions, but does knowing of Homer's Charybdis somehow

increase a reader's understanding of what Stephen is saying?

Late in the chapter, as Stephen stands across from Mulligan at

the front door of the library, he thinks, "

My will: his will

that fronts me. Seas between," and at that moment, "

A

man passed out between them, bowing, greeting." It is

Leopold Bloom, the Odysseus of this fiction, but is there any

symbolic significance in his sailing through a gauntlet of two

younger men? Bloom hardly figures in this chapter and neither

Stephen nor Mulligan is a dire threat to him, as his "bowing,

greeting" passage makes comically clear.

In less overt ways, though, the Homeric story does figure in the

chapter's intellectual structures. The "correspondences" listed

in Joyce's second schema suggest that he was thinking of Scylla

and Charybdis as emblematic of two broad conceptual oppositions.

"The Rock," Joyce wrote there, corresponds to "

Aristotle,

Dogma, Stratford" and "The Whirlpool" to "

Plato,

Mysticism, London." These intellectual groupings play an

important role in Stephen's thoughts. Russell and Eglinton, his

most formidable opponents, cultivate strains of mystical

spirituality and literary idealism that they associate with

Plato. Stephen prefers Aristotle's empirically oriented and

relentlessly logical "dagger definitions," arguing that the

function of literature is not to reveal a "world of ideas" but

to "Hold to the now, the here." Before the talk even begins, an

opposition is thus established between fiction that traffics in

abstractions and fiction concerned with empirical reality.

As Stephen begins his spiel, he maps these antinomies of

empiricism and mysticism, realism and idealism, onto the facts

of the playwright's life by investing Stratford and London with

psychological significance. Shakespeare experienced a searing

sexual betrayal in Stratford, he argues, and spent "Twenty

years" in London recoiling from that pain. His geographical move

effected a psychological divorce from sustaining family

connections. Exiled from home, Shakespeare became a spectral

shadow of his former self: "— What is a ghost? Stephen said

with tingling energy. One who has faded into impalpability

through death, through absence, through change of manners.

Elizabethan London lay as far from Stratford as corrupt Paris

lies from virgin Dublin."

But this alienation from human contacts—the

metaphor also implies a sundering of spirit from body—did

not release the playwright from his pain. Ghosts do not

enter a domain of mystical peace. They remain attached to

the unsatisfactory physical world.

Instead of pursuing escapist compensatory fantasy in his

fiction, Shakespeare spent his time in London writing about what

had happened in Stratford. Disappointed love was his devouring

Scylla, and he wrote about Anne Hathaway in play after play,

poem after poem. In

Hamlet, Stephen argues, the author

did not identify with Prince Hamlet, the idealistic young

dreamer half in love with "a consummation devoutly to be

wished." He wrote from the perspective of King Hamlet, a

murderously this-worldly ghost returning to the scene of the

crime in a hunt for vengeance. In his great tragedies

Shakespeare revisited Stratford in just this bloodthirsty way,

but by the time he wrote the late romances he had found a way to

return in a spirit of "reconciliation," healing the breach of

the original, generative "sundering." If Odysseus's story of

Scylla and Charybdis figures in this biographical narrative, its

arc has changed. Stephen's Shakespeare does not thread a needle

between opposed dangers. He journeys from Stratford to London,

and from London back to Stratford. "

He goes back."

Shakespeare's

works are filled with men who fear that the women they love

are unchaste, but few Shakespeareans will seek insights into

his plays and poems from Stephen's words.

Joyceans, however, will find many interesting insights into the

structures of

Ulysses in this chapter. Unlike

Shakespeare's protagonists, Bloom actually is a shamed cuckold

and must confront the possibility that his familial home is

irreparably lost. Stephen is an exile who has shamefully

returned: "Paris and back. Lapwing. Icarus." Joyce did the same,

but later left Dublin for good and recreated it, brick by brick,

in imagination. The novel's ghostly author creates an entire

world of remembered people through the eyes of his avatars, just

as Shakespeare did looking back on Stratford. "His own image to

a man with that queer thing genius is the standard of all

experience, material and moral." The pattern of exile and return

is one way in which Stephen's Shakespeare talk lays out a kind

of conceptual roadmap for the novel at whose center it sits.

There are others.

For the materials for his argument, Stephen is indebted not only

to many of Shakespeare's works but to three works of

Shakespearean biography and criticism. Sidney Lee, an English

biographer and critic, published

A Life of William

Shakespeare in 1898 and saw it through four more editions

by 1905.

The Man Shakespeare and His Tragic Life Story, by

the Irish-American man of letters Frank Harris, was not

published until 1909, but Harris printed much of it in the

prominent London periodical

Saturday Review which he

edited from 1894 to 1898. The important Danish literary critic

Georg Brandes published his widely acclaimed

William

Shakespeare: A Critical Study in 1898, in an English

translation by William Archer. The influence of these works can

be seen in particular details of Stephen's argument. Of the

three, the greatest number of borrowings probably come from Lee,

but the most powerful intellectual influence may be Brandes.

Like the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, Brandes despised

fantasy, idealism, and mere aestheticism, arguing that in the

modern era literature needed to provide piercingly realistic

representations of life. Joyce greatly admired both writers. As

a young man he regarded Ibsen's dramatic works as supreme

monuments of literary truth-telling, relegating Shakespeare to

second class. But by the time he was working on

Ulysses

he apparently had decided that the English playwright deserved

his colossal reputation. Stephen presents him as a kind of

archetypal literary creator, famed for the usual reasons: he

brought hundreds of fictional people to life and through them

communicated deep insights into human thought and behavior. But

his Shakespeare is not a sage contemplating disembodied truths

in the manner of George Russell. Largely "untaught by the wisdom

he has written or by the laws he has revealed," he writes

because he has to. Every work is a confrontation with the

green-eyed monster savaging his emotional life.

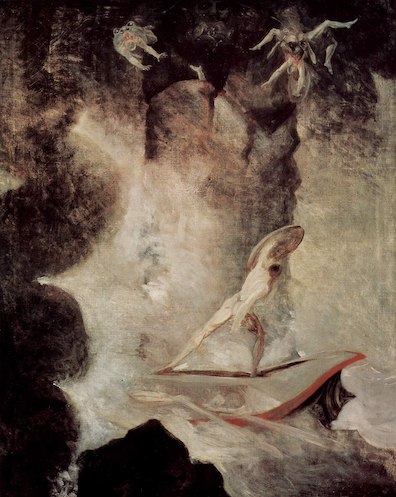

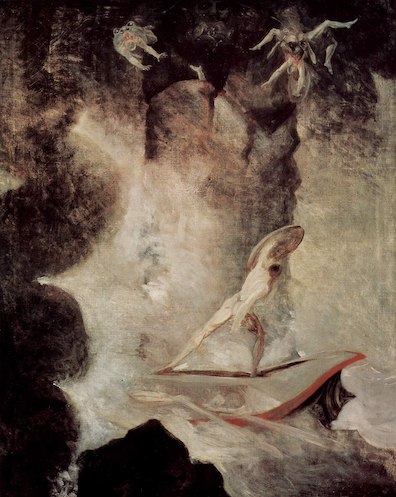

Oil on canvas painting by Henry Fuseli ca.

1794-96 showing Scylla snatching men off the ship, held in the

Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau, Switzerland. Source: Wikimedia

Commons.

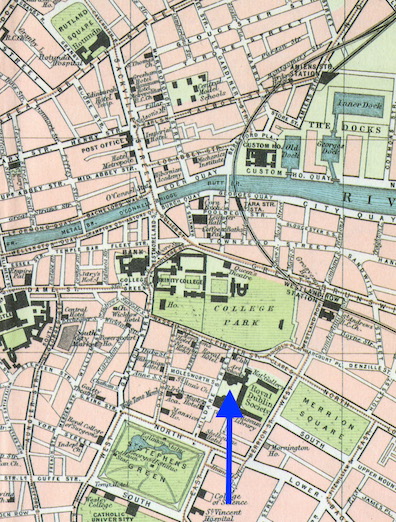

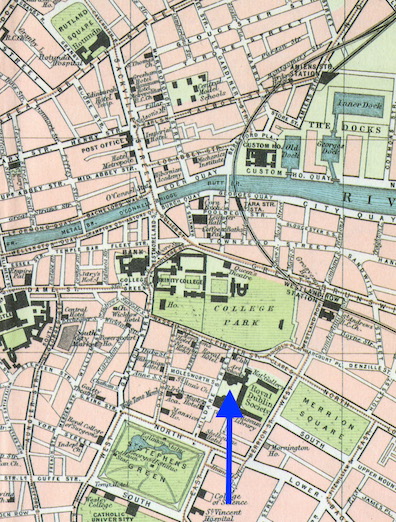

Detail of a Bartholomew map of Dublin, with

added arrow showing the location of the National Library.

Source: Pierce, James Joyce's Ireland.

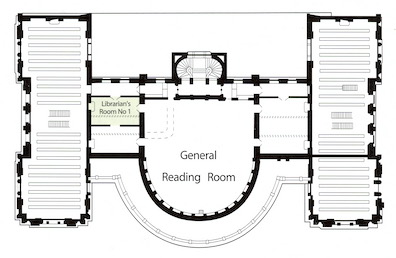

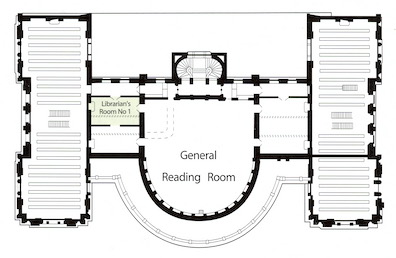

Plan of the library's first floor showing the

librarian's office where most of the chapter takes place.

Source: Gunn and Hart, James Joyce's Dublin.

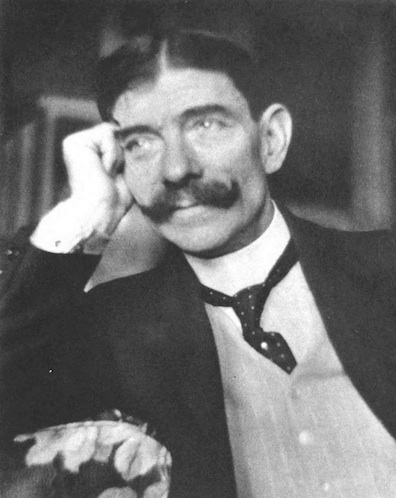

1901 photograph of Sidney Lee, born Solomon Lazarus Lee .

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Cropped detail from Alvin Langdon Coburn's 1913 photograph of

Frank Harris. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ludwik Szaciński's ca. 1890-1900 photographic portrait

of Georg Morris Cohen Brandes. Source: Wikimedia

Commons.