Acting "unostentatiously" (i.e., discreetly or covertly—the

language of Eumaeus is often not quite right), Bloom

turns over the postcard and notes a "partially obliterated

address and postmark": "Tarjeta Postal, Señor A Boudin,

Galeria Becche, Santiago, Chile. There was no

message evidently, as he took particular notice." His

particularly noticing the lack of a message is made to sound

astute, but in fact the absence of one on the back of a

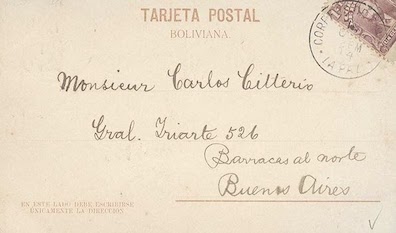

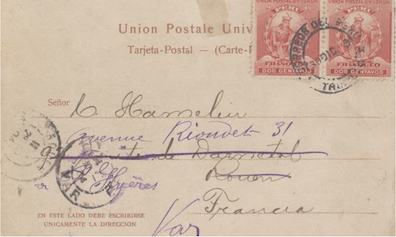

postcard would not have been remarkable in 1904. In a JJON

article, Aida Yared suggests that before 1907 it would have

been remarkable if any message had been written there.

Postcards, she notes, traditionally had an "undivided back,"

sometimes with instructions to write nothing but the address

of the recipient there. She reproduces the backs of two 1904

postcards ("Tarjeta Postal"), one from Bolivia and another

from elsewhere in South America, whose lower left corners tell

users not to crowd the blank space with anything else: "En

este lado debe escribirse unicamenta la direccion" ("only the

address should be written on this side").

There is something suspicious about the name, though. Murphy

has said that "A friend of mine sent me" the postcard, so his

name should be on the back, but instead it is addressed to a

Señor Boudin. Bloom evidently prides himself on "having

detected a discrepancy between his name (assuming he was the

person he represented himself to be and not sailing under

false colours after having boxed the compass on the strict

q.t. somewhere) and the fictitious addressee of the missive

which made him nourish some suspicions of our friend's bona

fides." There certainly is a "discrepancy," and it

does suggest that Murphy is not being entirely truthful, but

why assume that the addressee is "fictitious"?

None of the logical possibilities seem very plausible. Murphy

could have bought or otherwise acquired a used postcard, in

which case he would be lying about a friend mailing it to him,

but not about the name of the recipient. Or he could be

telling the truth about receiving the card in the mail but

lying about his own name, which is actually Boudin—which would

be a strange name for an Irishman from County Cork, unless he

is Huguenot. But if, as Bloom provisionally assumes, his name

really is Murphy, why would the name on the card be made-up?

Did Murphy receive mail at a poste restante in

Santiago as Boudin, just as Bloom does on Westland Row as

Henry Flower? How would Bloom know that? If there is some

brilliant deduction going on in his mind, it is not made

apparent in the narrative.

Still, it is hard to ignore the invitation to regard "Señor

A Boudin, Galeria Becche, Santiago, Chile" as

"fictitious," because the address does not sound quite

convincing. Boudin is not a surname in Spanish-speaking

countries, though it is in France. The French word refers to

the kind of blood sausage that the English and Irish call a

"black pudding." (There is also a boudin blanc, a

finer-textured sausage that unlike the black boudin

contains no blood.) Reading the addressee as "A Sausage" is

supported by the possibility that the word "Señor" may not

have been written on the card. Yared notes that some South

American postcards sexistly pre-printed "Señor" at the

beginning of the address space—seen on one of the cards shown

here. Also, in the Rosenbach manuscript and the Gabler

edition, "A" is written without the period that should follow

an initial, allowing it to be read as an indefinite article.

(Although British usage omits the full stop when letters are

subtracted from the middle of a word, as in Fr for Father, it

requires it when the elision comes at a word's end. In Eumaeus

Bloom becomes L. Boom, not L Boom.)

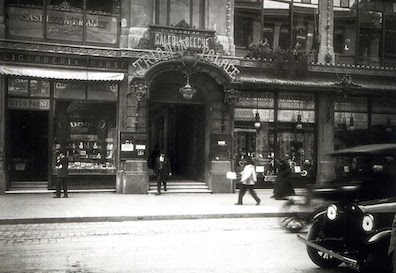

A similar not-quite-rightness attends the address. There was

an actual commercial arcade in downtown Santiago with almost

the name on the postcard: in another JJON article,

John Simpson reports that a Chilean businessman named Hector

Beeche (or Beéche) commissioned the construction of a large

building (one full city block, four stories) with a

first-floor internal passageway called the Galería Beeche

offering spaces for offices and elegant shops. But the

spelling was "ee," not "ec." The Beeche Building did not come

into existence until 1909, so the choice to set the address

there may have been driven less by a desire for mimetic

accuracy than for an opportunity to pun on its name. Again,

food resonances present themselves: in Italy a beccheria (synonymous

with macelleria) is a butcher's shop.

It seems possible, then, that someone has asked the postal

service to deliver the card to a sausage in a meat store. If

so, nothing about the conceit—referencing an actual landmark

in a Hispanic city but changing one letter of its name to

accommodate an Italian pun, and linking the address with a

French surname which contains a similar pun in that language,

all in the service of making a sophomoric joke—sounds like

something that the dull-witted D. B. Murphy might have dreamed

up. It does, however, sound very much like the fictive work of

James Joyce. Another postcard in Ulysses, the

meanspirited U.P. missive that

rouses Dennis Breen to fury and sends readers off in search of

ingenious explanations, signifies very little in itself but

means quite a lot to others. Joyce may be doing something

similar with the back of Murphy's postcard: having a lark in a

way that teases the earnest Bloom into a hunt for meaning.