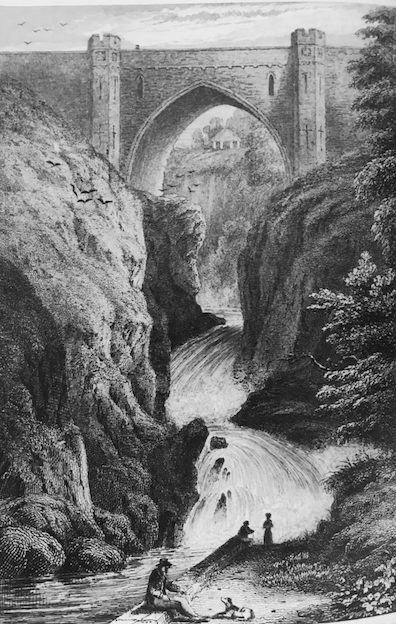

Poulaphouca (Irish Poll an Phúca, the Hole of the

Pooka) gets its name from a race of mischievous and sometimes

malevolent Irish spirits. A pooka lived in the Wicklow

waterfall, which used to plunge some 150 vertical feet through

a rock chasm about 40 feet wide. 18th and 19th century

guidebooks recognized the site's appeal as a tourist

destination and roads were built to it, as well as a bridge

crossing the chasm. In May 1895 the Dublin and Blessington

Steam Tramway opened a new line to the site called the

Blessington and Poulaphouca Steam Tramway, which Bloom thinks

of in Eumaeus: "Poulaphouca to which there was a

steam tram." But construction of a hydroelectric dam in

the 1930s and 40s reduced the waterfall almost to nothing.

During his hallucinatory conversation with the Nymph who

hangs over his bed, Bloom mentions the commode and chamberpot in the bedroom:

"That antiquated commode. It wasn't her weight. She scaled

just eleven stone nine. She put on nine pounds after weaning.

It was a crack and want of glue. Eh? And that absurd

orangekeyed utensil which has only one handle." Immediately

after these recollections of Molly making water, "The

sound of a waterfall is heard in bright cascade,"

speaking the word, "Poulaphouca Poulaphouca / Poulaphouca

Poulaphouca." The waterfall is imaginatively fused,

then, with a cascade of urine, and immediately afterward

thoughts of sexual excitement are introduced by a stand of

distinctly female yew trees that "grew by the Poulaphouca

waterfall."

Coyly mingling their boughs, the Yews whisperingly ask, "Who

came to Poulaphouca with the high school excursion? Who left

his nutquesting classmates to seek our shade?" It was Bloom,

and as he starts to reluctantly confess his sin the waterfall

sounds again, its refrain now slightly altered: "Poulaphouca

Poulaphouca / Phoucaphouca Phoucaphouca." The

subset of readers who may have heard the word "fuck" in the

initial mention of the waterfall may now find their dirty

minds vindicated by the relentless repetition of that

syllable. The Nymph exclaims, "O, infamy!" Rousing himself to

self-justification, Bloom pleads immaturity: "I was

precocious. Youth. The fauna. I sacrificed to the god of the

forest. The flowers that

bloom in the spring. It was pairing time. Capillary

attraction is a natural phenomenon. Lotty Clarke,

flaxenhaired, I saw at her night toilette through ill-closed

curtains, with poor papa's operaglasses."

This is one of those torrents of flimsy excuses that define

Bloom's reactions to public shaming throughout Circe.

He blames his erection on teenage hormones interacting with

natural surroundings: countryside, springtime, trees and

flowers, birds and bees. His amateur mania for scientific

"phenomena" produces a particularly absurd claim: that fluid

rose in his penis by "Capillary attraction," either on its own

or in sympathy with the sap rising in the nearby plants. Only

his final excuse, that his excitement had something to do with

spying on a neighborhood girl as she urinated, has the ring of

confessional truth. The Poulaphouca scene thus closes as it

began, with the waterfall provoking lust by calling up

memories of a woman peeing.

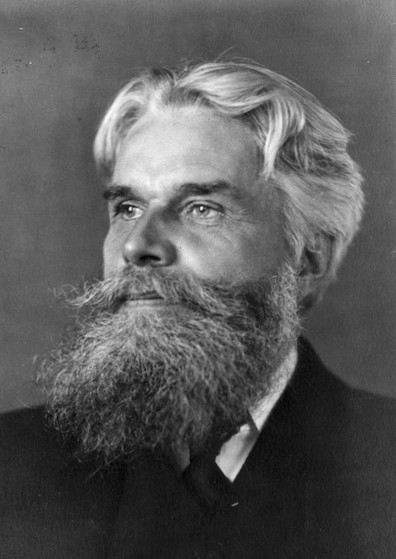

In writing Circe Joyce drew on several contemporary

and near-contemporary "sexologists"—writers whose

investigations of human sexuality delved forthrightly into

phenomena customarily regarded as perverse. One was Havelock

Ellis, an English physician who produced nonjudgmentally

probing accounts of homosexuality (he preferred the term

"inversion"), autoeroticism (a much more complex phenomenon

than just masturbation), transvestism (which he called

"eonism"), and other peculiar forms of sexual preference.

Ellis discovered one such psychosexual complex from personal

experience when, at age 60, he found himself aroused by the

sight of a woman urinating. He called this proclivity

"undinism."

The term came from undines: female water spirits dwelling in

forest pools and waterfalls, first hypothesized by Paracelsus

in the 16th century. By the time Ellis wrote in the early

20th, the mythology had become firmly fixed in the popular

imagination. Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's fairy-tale novella

Undine (1811) had given rise to dozens of stories,

novels, plays, paintings, sculptures, and musical compositions

in the 19th century. (The mythology has continued to inspire

artistic works down to the present day. The 21st century has

seen production of two films film called Ondine and Undine.)

Most of these works represent undines as female water-spirits

who chance to take a sexual interest in human males. The more

one learns about the mythology, the more relevant it seems to

the elements that Joyce combined in his Poulaphouca passage: a

naked goddess found in or near water ("The Bath of the Nymph"), a

waterfall named for a resident spirit, female tree spirits,

heterosexual attraction, and urination.

Did Ellis influence the writing of this passage? Joyce

admired his works greatly and had only begun to write Circe

when Ellis experienced his strange attraction in 1919. But as

far as I can determine Ellis did not publish his theory of

undinism until volume 7 of Studies in the Psychology of

Sex, which came out in 1928. Until it can be shown that

Joyce somehow learned of it by 1920, when he finished the

Nighttown chapter, any suggestion of influence must remain

speculative. If Joyce did not know of the psychological term,

perhaps he conceived of something very similar independently.

His Trieste library contained a copy of de la Motte Fouqué's Undine.

Joyce scholars do not seem to have recognized the Ellis-like

connection between urine and sexual excitement in Circe, but

at least one has come close. In James Joyce and Sexuality

(1985), Richard Brown writes, "Ellis connected his interest in

eroticism and urination with more general sexual fondness for

water and bathing for which he coined the term 'Undinism'.

There might seem to be plenty of this in Joyce's work from

Stephen's bed-wetting and the wading girl in A Portrait,

and Bloom's bath in Lotus-Eaters, to 'St Kevin

Hydrophilos' in Book IV of Finnegans Wake" (84). Brown

goes on to talk about Ellis's interest in voyeurism and

Bloom's watching Lotty Clarke "through illclosed curtains,"

but he does not remark on the link between chamberpots and

waterfalls.

Many pages of Circe are devoted to Bloom's scandalous

and uproariously embarrassing sexual peculiarities. In some

passages the analysis seems almost clinical, as when the

doctors from the hospital common room subject him to rigorous

examination. But the Poulaphouca passage is built on more

literary and mythological materials. Richard Brown aptly

observes that both Joyce and Ellis "were prepared to look at

sexual anomaly not just as matter for clinical examination

but, to some extent, as an aspect of human creativity and

imagination" (85). The word "undinism" seems perfectly, and

perhaps even uniquely, suited to what Joyce makes prose do in

this scene.

In keeping with that observation, it should also be noted

that the fixations that Bloom displays in the Poulaphouca

episode are relatively inoffensive. Ellis coined another term

for his proclivity, "urolagnia" (urine-lust), that has been

more widely embraced in our coarser culture. (Perversities

such as "golden showers" were perhaps no less commonly

practiced behind closed doors a century ago, but they were

much less commonly discussed.) But Bloom does not fantasize

about peeing on someone, or being peed on, or drinking urine.

He seems to be turned on by the mere sound of

urination, by the mere association of a woman's body

with moving water, and by a mere fancy of female

spirits inhabiting the woods and waters. His attractions to

this watery dimension of female physicality are mercifully

notional in comparison to the anal fixations that Ellis termed

"coprolagnia." There, his confessions enter darker terrain: "I

rererepugnosed in rerererepugnant..."

The thoughts explored in this note were kicked off by a

personal communication from Vincent Van Wyk, who urged me to

consider the possibility that Bloom masturbates in the woods

because he connects the sound of the nearby waterfall to

Molly's urination and is sexually aroused by it. While no one

else seems to have explicitly commented on the connection

between the two kinds of rushing water, some have probably

intuited it. Vladimir Nabokov (as recorded in Alfred Appel,

Jr.'s annotations to Lolita) remarked that "Havelock

Ellis was an 'undinist', or 'fountainist', and so was Leopold

Bloom" (425). And so too was James Joyce. Ellmann's biography

records the fact that, in a letter he wrote to Gertrude

Kaempffer in Zurich, Joyce described his first sexual

experience, at age 14. He was walking through rural fields

with the family nanny when she excused herself and asked him

to look away. "As he did so he heard the sound of liquid

splashing on the ground.... The sound aroused him: 'I jiggled

furiously', he wrote" (418).